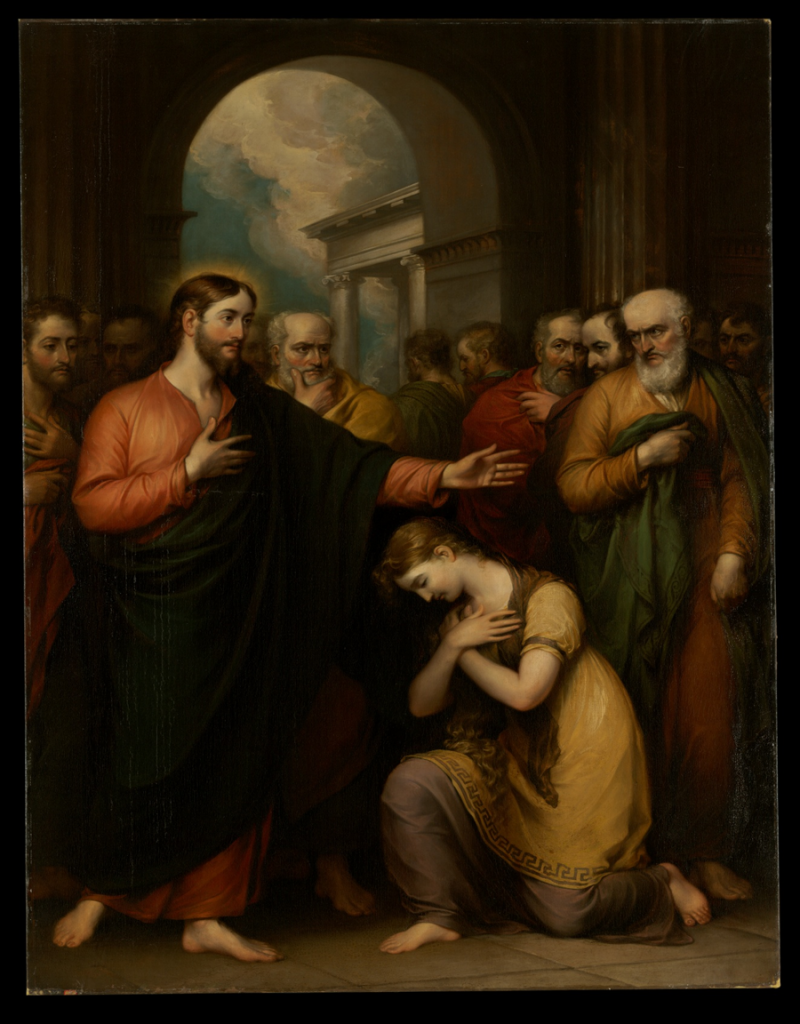

Living in England, trying to sustain them financially painting portraits of well-to-do society members, Trumbull also tried his hand at many religious and some political scenes. One of the best examples is “The Woman Taken in Adultery,” painted in 1811. This is a large painting measuring almost 8 feet tall and five feet across. Trumbull has painted Harvey as the adulterous woman, and she kneels before Christ with her hands crossed over her heart. Dunlap said that this painting was one of the best pictures painted by an artist of this period. [1]

Harvey wears a dull yellow tunic featuring a Greek motif at the knee. This tunic is worn with an underlay of grey-blue that reaches the floor. Harvey, as the adulterous woman, has a scarf draped around her neck that is bronze, and her sleeves bear a matching cuff of this fabric. Her pale skin stands out on the dark canvas as her head is bowed, her neck is borne and her bare feet on the stone tiles. The scene is a typically Roman-looking scene with marble columns and arches framing the action. Christ stands in the front left of the painting with his arm outstretched over the woman in a gesture of forgiveness and his other hand laying over his heart. He is wearing a red- toned tunic with a dark cloak draped over one shoulder and arm. Twelve other men are standing in the area around Christ in varying poses from disbelief to acceptance. Some stand and stare while others have turned away to leave. The painting feels like a moment frozen in time as if you could press play and watch the rest of the scene play out.

This painting shows the well-known biblical scene of a woman caught in adultery by the Pharisees who pester Christ to condemn her. This woman, rumored to be Mary Magdalene, waits for the condemnation that never comes. Instead, Christ asks the men, “Who among you who is without sin, may cast the first stone?” and the men disperse. [2] Trumbull painted this painting when he was living in England with Harvey and making his living from portraiture. The religious paintings proved a way for Trumbull to stay current with his craft, even if they were not bringing in much money.

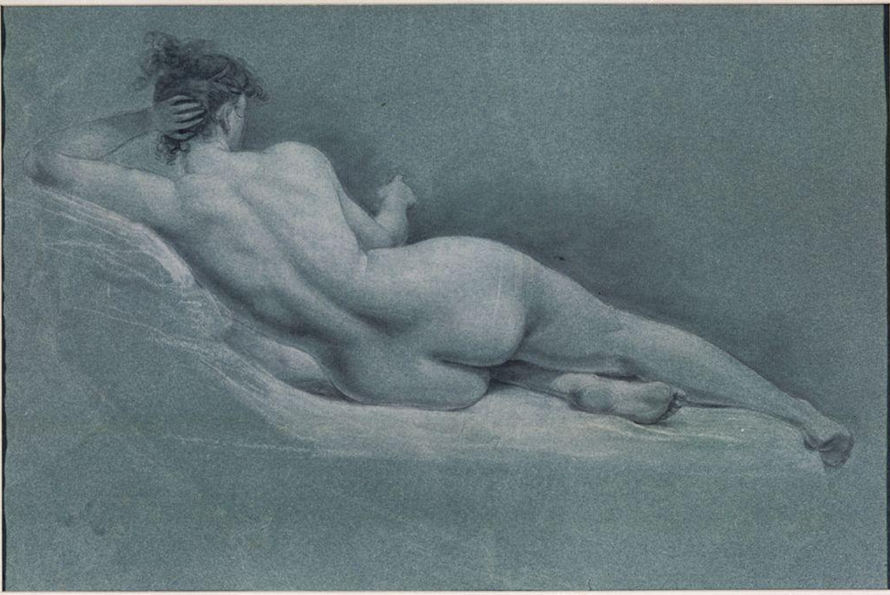

This painting has an interesting story connected with it. It is said that Trumbull and Harvey were enjoying a quiet evening at home. Harvey was sewing and dropped her scissors on the floor. When she knelt to retrieve them, Trumbull stopped her. He was captivated by her position and asked to sketch her. This is the beginning sketch of this painting. [3]

Later in America, this painting would take on a darker tone. It appears that Harvey did not drink to excess until the second time that they went to live in the States, in 1815. Historian Theodore Sizer suggests that Harvey’s dependence on alcohol probably stemmed from homesickness, feeling out of place, and depression. [4] In the terse letter that Trumbull wrote to his niece in 1806 detailing what he considered to be ill-treatment by his family, Trumbull showed that he harbored some fears when moving back to America. [5] Trumbull might have felt some responsibility for her depression when they returned, and things were not working out well for her. Even still, rumors and gossip began to fly around Harvey and her conduct. She was not fitting in with Trumbull’s high society friends.

In a letter dated 1817 from Trumbull’s friend King wrote to Gore about a party that went disastrously for Harvey. In the letter, King describes a high society get-together for the French Ambassador, Jean-Guillaume, Baron Hyde de Neuville. King was descriptive of an elegant party with delicious food spread over tables and guests milling around. King, after mingling with the party-goers found an out-of-the-way chair in a nook next to the Portugues ambassador for some quiet conversation. King looks up to see Col. Trumbull and “Mrs. T” walking towards him.

Harvey was obviously intoxicated at this point. King describes that she “quitted her husband’s arm, and sallying towards me, almost tumbling into an empty chair on my right. She immediately began in expressions of joy on having found me; told me how much she esteemed me, hoped I was her friend and her husband’s friend; and under pretense of low conversation put her mouth to my ear …all who passed halted to observe our tete-a-tete.” [6]

Soon, Gore reported, Harvey moved on to Senator-elect Harrison Gray who she asked about Harvey, Gore saying, “Is he any better?…he is one of my best friends, he is my father, he gave me to my husband, Oh, how much I love him; he is my husband’s friend, and I love him even more for that, than for anything else.”

Later in the party, the letter reported that Harvey had words with two women who were gawking at her conduct. Harvey turned to one and said, “What do you see, what do you look at me for; what are you staring at?” Another woman watching the scenes asks who the belligerent woman is, and it is replied, pointing at Trumbull, “There is her husband. King describes Harvey like a tigress leaped on the woman saying, “What business have you with my husband, what are you looking at him for? What is it to you that he is my husband?” Then, in a group, the society folks turned on her and walked away. [7] Trumbull and Harvey seemed to have left the party early before supper soon after.

King went on to write about the scene the following day. He saw Trumbull and wanted to speak about all the mishaps from the night before, but Trumbull gave him no chance or opening to bring up the matter. Trumbull seemed to be his normal self. King reported that Trumbull had no “mortification on his countenance.” King intended to explain to Trumbull that Harvey’s conduct reflected poorly on his own character. King wrote that Trumbull’s amiable countenance and polite manners, joined to the uncertainty of how such a communication would be received, discouraged me and we parted as usual, except that I could not bring myself to make the usual inquiry concerning his wife.” [8] King finished the letter saying that on account of Harvey’s conduct, she would be certain to be excluded from all future civilities here.

A letter from Edward Fenno, son of the editor of the Gazette of the United States, to his sister, Eliza describes a similar scene with Harvey. The letteris dated 1816. It reads in part, “Mrs. Col. Trumbull was at one of the assemblies. She was irregularly dressed and looked like a washwoman. She was so drunk at Mrs. Primes party that they were obliged to carry her home.” [9] Another letter dated from 1823 reads, “[we] took a carriage to Uncle Trumbull’s…I was received with great kindness from Uncle, and treated by his wife in her best manner, tho she looked very bad and had evidently been indulging too much.” [10] One more letter by a Margaret Fuller reads, Harvey’s “coarse and imperious expression reflected her low habits of mind, and her exaggerated dress and gesture betrayed her lack of education. At dinner Mrs. Trumbull drank glass after glass of wine and became abusive. Colonel Trumbull asked the host to forgive him. He had married, he explained, to atone for a sin.” [11] Letters and gossip like this spread quickly and it wasn’t too long before all high society at the time considered Harvey unwelcome. In another instance, a letter dated 1819 reads, “I see little of Col. Trumbull but you knew his misfortunes. His terrible wife repels all society from his house and he lives in a sort of stately misery.” [12]

[1] Cooper, Helen A., editor. John Trumbull: The Hand and Spirit of a Painter.

[2] Holy Bible. John Ch.8, vs 7. New International Version, Zondervan, 2011.

[3] Brookhiser, Richard. Glorious Lessons: John Trumbull, Painter of the American Revolution.

[4] Sizer, Theodore. “The Autobiography of Colonel John Trumbull, Patriot-Artist.”

[5] Sizer, Theodore. “The Autobiography of Colonel John Trumbull, Patriot-Artist.”

[6] Brookhiser, Richard. Glorious Lessons: John Trumbull, Painter of the American Revolution.

[7] Brookhiser, Richard. Glorious Lessons: John Trumbull, Painter of the American Revolution.

[8] Brookhiser, Richard. Glorious Lessons: John Trumbull, Painter of the American Revolution.

Sizer, Theodore. “The Autobiography of Colonel John Trumbull, Patriot-Artist.”

[10] Sizer, Theodore. “The Autobiography of Colonel John Trumbull, Patriot-Artist.”

[11] Sizer, Theodore. “The Autobiography of Colonel John Trumbull, Patriot-Artist.”

[12] Gulian Crommelin Verplanck to Washington Allston, New York, May 18, 1819 in Nathalia Wright, ed., The Correspondence of Washington Allston (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1993), 156.